by Kathleen Austin & Gerald Kendall

Part 1 provided an introduction to projects and the need to plan a project.

Summary: Project networks are the building blocks to complete a project successfully. If you don’t have enough building blocks and you have to get more during execution, the project likely fails to meet its time and cost projection. If the blocks are made of poor material (poor understanding of the work), they will crumble during execution. If we don’t understand which blocks go where, and which blocks are needed before we can put the next ones in place, we’ll have a lot of rework. From experience, it is worth the effort to have and use a formal process for both constructing and for scrutinizing networks.

We (Kendall & Austin, Advanced Multi-Project Management, J.Ross Publishing, 2012) have not heard of a single case of any organization getting predictable results from projects without having a rigorous project plan, constructed using a disciplined and consistent process. This implies that the process cannot be left up to each individual project manager to determine from their own experiences. To end up with a good end product, you must not only follow the process, but also have the right people involved in the network building process.

Part 2: How to Ensure the Correct Level of Detail in a Project Network

Hint: It’s not the lowest level of the Work Breakdown Structure!

Oh, I remember the days as a brand-new 2nd Lt working program control and project management on an Air Force weapons acquisition system. I was so sure I was right, following the requirement to insist defense contractors plan the project work to seven levels and report monthly (in the earned value system) at level three. And then, not being able to answer my boss’s questions about how the projects were really doing in terms of schedule and cost variance. What did “green” mean in terms of project due date and budget? What was “yellow” and what was “red”? We had a great reporting system, metric-rich and full of detail – but it didn’t help us at all to manage the work, nor could we really tell, based on the reports, where the projects were in terms of completion. Truly it was like driving a car forward, on a busy freeway (Atlanta or LA) with only a rear-view mirror. YIKES!!

What a dilemma planning a project can be! Expectations for project plans usually include many of the following:

- Usable for costing the project,

- Structure to track while executing the project,

- Doing resource loading,

- Calculating earned value,

- Detailing exactly what every task should be and/or should include,

- Providing information about inputs for the task,

- Defining each task’s exit criteria,

- Describing any specific notes or details about each and every task,

- Enabling managers to know who are the primary performing resources (people, equipment, facilities) and who are supporting resources (those not used for the entire time of the task, but required to achieve the tasks’ exit criteria, etc.)

Don’t forget, the project plan must also include all the work required to meet the stakeholders’

consensus of project scope. Oh yes, a project plan should also be easy to manage!

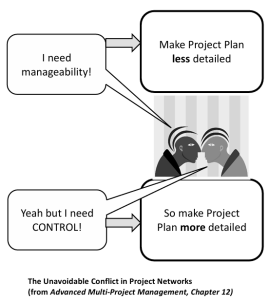

It is easy to see the conflict for project planners:

On one hand, in order to assure project success, the project plan must be manageable, which means there’s pressure to not have a very detailed project plan (because otherwise it would not be manageable – the focus would be diluted on too many tasks).

On the other hand, in order to assure project success, the project plan must provide all the data needed during project execution (to manage resources, work, costs, timelines, estimates to complete, etc.), which means there’s pressure to have a very detailed project plan. It sure sounds like a project plan is being used for more than planning, scheduling, executing, and managing a project – it’s also required to be the entire project database! Is that reasonable?

It’s not unusual for project organizations to provide a way out of the conflict for project planners: no more than 350 tasks; no task is longer than 80 hours; plan at a very low level of detail of the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS), but manage at a much higher level (see box above!). Have these approaches been effective for all projects? Our answer is, “Definitely not.” (Sounds more like coping mechanisms and compromises, doesn’t it?)

In our opinion, there is a huge problem with using the WBS as the project plan, the way that it is implemented in most of the circumstances we have seen. WBS is defined by the Department of Defense as an organized method to breakdown a product into sub-products at lower levels of detail.1 These sub-products do not represent the interdependencies of work required to create the product. However, one of the big risks in doing project work is in the handoffs between resources and the interdependencies between tasks. When there is so much detail with sub-products, you lose focus on these interdependencies.

We recommend doing project planning by creating a project network – an interdependent relationship of tasks (boxes) and flow of work (arrows) that are required in order to achieve the goals, scope, and sponsor criteria of the project. (More on actual building of the project network in upcoming blog posts)

The less detail/more detail conflict exists for project planning. Our solution is to approach project planning from this perspective: Start planning at a high-level, then “explode” the plan into more detail only when and where needed.

The 10 Step Process

The 10 steps to build a robust network at the right level of detail to meet stakeholder needs with minimum risk are:

- Define the project’s measurable goals, tangible scope and sponsor

- Define the backbone of the

- Expand the skeleton of the network

- Define additional dependencies

- Check the network against project goals, scope and deliverables

- Scrutinize with subject matter experts

- Resource the project tasks

- Estimate time durations

- Reduce duration without compromise

- Perform a final risk assessment

Conclusion

There are two commonly used approaches to project planning, both of which do not work well. One is “seat of the pants” where projects are run without a formal, written, scrutinized plan. The other is a plan worked to the lowest level of detail of a work breakdown structure. Such a plan is so detailed that the underlying problems are masked and the plan is very difficult to scrutinize. In the 10 step process outlined here and defined in the upcoming posts, detail is only advocated where absolutely necessary because there are task interdependencies or other crucial elements of scope. We believe excessive detail does not help control a project – in fact, the outcome is often the opposite. This belief is backed up by years of experience with organizations who have used this process to build project networks with much greater than average project success.

Reference:

- Department of Defense Standard Practice, MIL-STD-881C, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, 3 October 2011, 4.

Next Post

Step 1: Define the project’s measurable goals, tangible scope and sponsor criteria.